part of Course 193 How Neural Networks Work

Find the rest of the How Neural Networks Work video series in this free online course.

What is it that neural networks actually learn?

Neural networks are famously difficult to interpret. It’s hard to know what they are actually learning when we train them. Let’s take a closer look and see whether we can build a good picture of what’s going on inside.

Just like every other supervised machine learning model, neural networks learn relationships between input variables and output variables. In fact, we can even see how it’s related to the most iconic model of all, linear regression.

Linear regression

Linear regression assumes a straight line relationship between an input variable x and an output variable y. x is multiplied by a constant, m, which also happens to be the slope of the line, and it’s added to another constant, b, which happens to be where the line crosses the y axis.

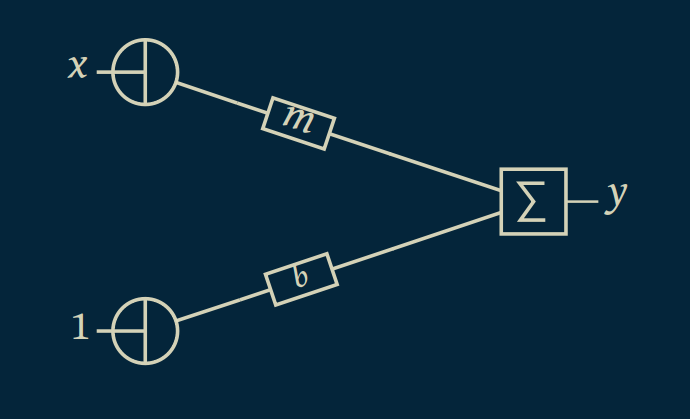

We can represent this in a picture. Our input value x is multiplied by m. Our constant b, is multiplied by one. And then they are added together to get y. This is a graphical representation of y equals mx plus b.

On the far left the circular symbols just indicate that the value is passed through. The rectangles labeled m and b indicate that whatever goes in on the left comes out multiplied By m or b on the right. And the box with the capital sigma indicates that whatever goes in on the left gets added together and spit back out on the right.

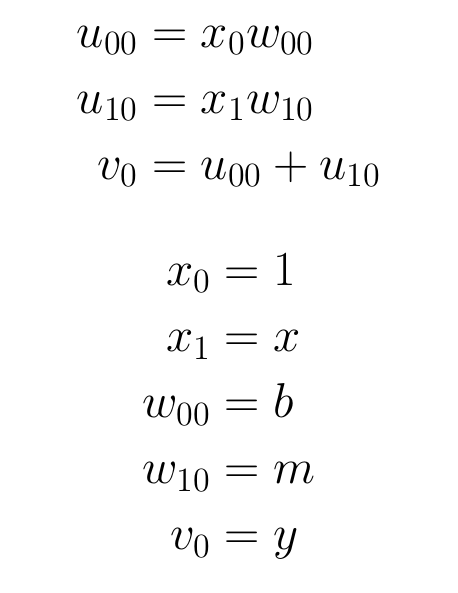

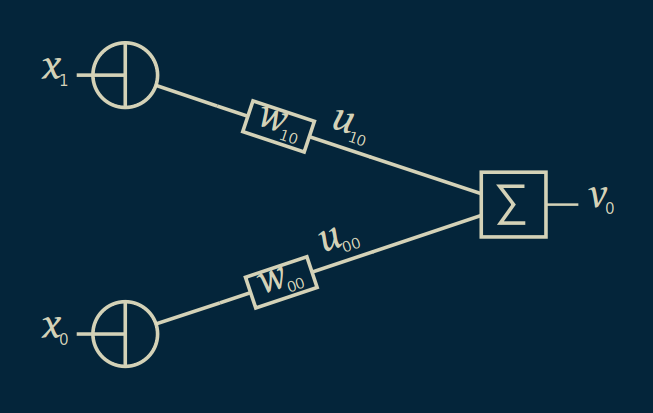

We can change the names of all the symbols for a different representation.

This is still a straight line relationship. We have just changed the names of all the variables. The reason we're doing this is to translate our linear regression into the notation we use in neural networks. This will help us keep track of things as we move forward.

At this point, we have turned a straight line equation into a network. A network is anything that has nodes connected by edges. In this case x_0 and x_1 are our input nodes, v_0 is an output node, and our weights connecting them are edges. The mathematical term for a construct like this is a graph. This is not the traditional sense of a graph, meaning a plot, or a grid like in a graphing calculator or graph paper. It’s just the formal word for a network, for nodes connected by edges. Another piece of terminology you might hear is directed acyclic graph, abbreviated as DAG. A directed graph is one where the edges just go in one direction. In our case, input goes to output, but output never goes back to input. Our edges are directed. Acyclic means that you can’t ever draw a loop. Once you have visited a node, there is no way to jump from edges to nodes to get back to where you started. Everything flows in one direction through the graph.

We can get a sense of the type of models that this network is capable of learning by choosing random values for the weights, w_00 and w_10, then seeing what relationships pop out between x_1 and v_0. Remember that we set x_0 to 1 and are holding it there always. It is a special node called the bias node.

It should come as no surprise that the relationships that come out of this linear model are all straight lines. After all, we’ve taken our equation for the line and rearranged it, but we haven’t changed it in any substantial way.

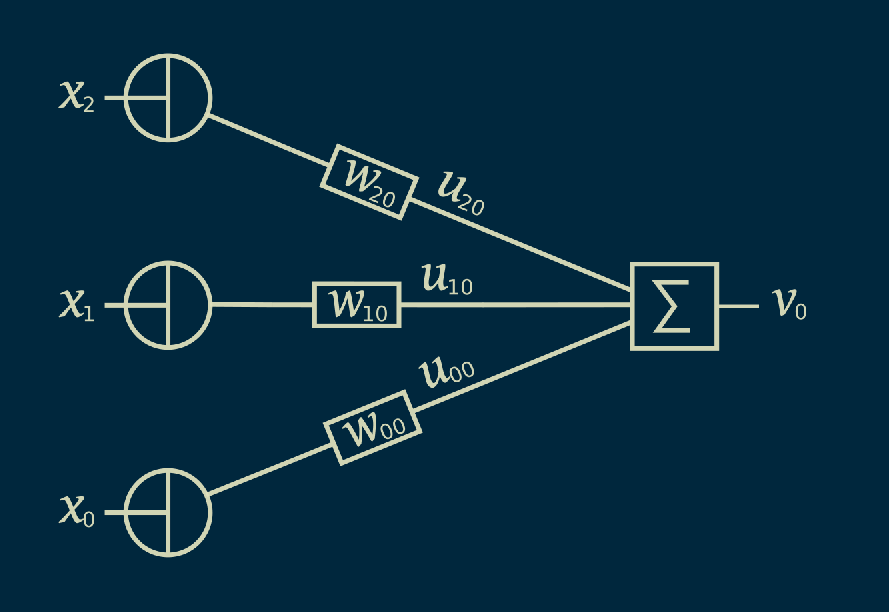

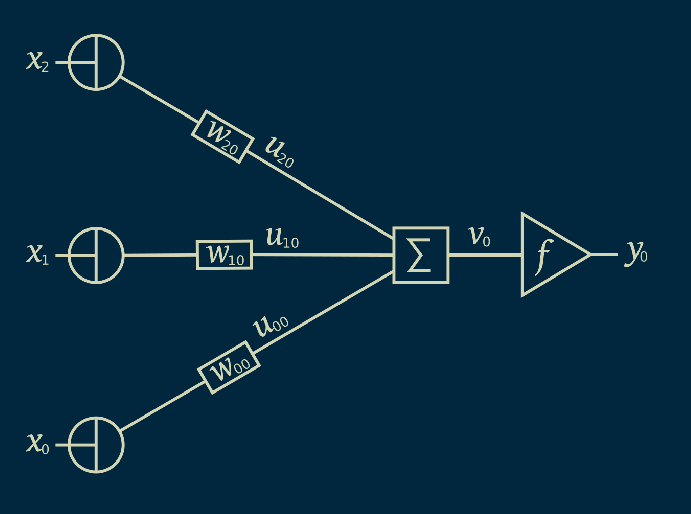

There’s no reason we have to limit ourselves to just one input variable; we can add an additional one. Now we have an x_0, an x_1, and an x_2. We draw an edge between x_2 and our summation with the weight w_20. x_2 times w_20 is again u_20 and all of our u's get added together to make a v_0.

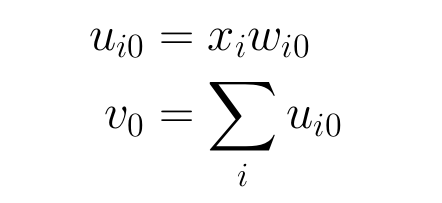

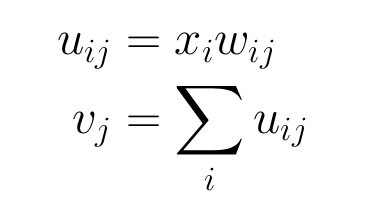

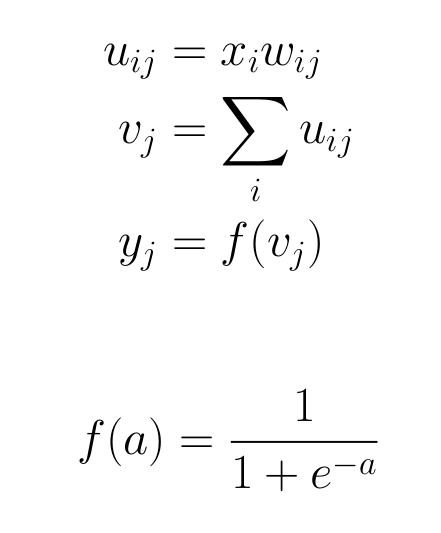

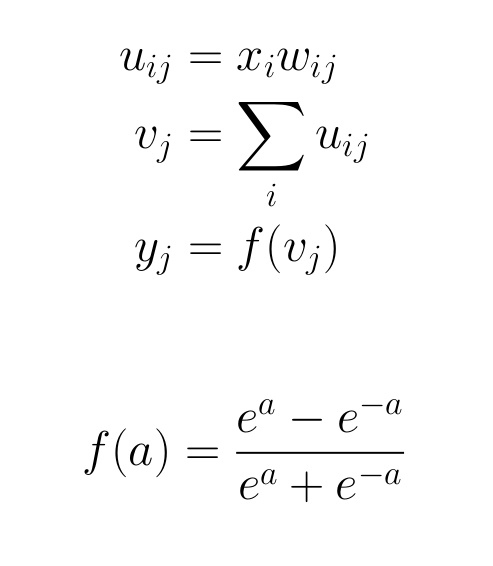

And we could add more inputs. As many as we want. This is still a linear equation, but instead of being two dimensional, we can make it three dimensional or higher. Writing this out mathematically could get very tedious, so we will use a shortcut. We'll substitute the subscript i for the index of the input; it's the number of the input we are talking about. That allows us to write u_i0, where our u_i0 equals x_i times w_i0, and again our output V_0 is just the summation, over all values of i, of u_i0.

For this three dimensional case, we can again look at the models that emerge when we randomly choose our w_i0’s, our weights. As we would expect, we still get the three dimensional equivalent of a line, a plane. And if we were to extend this to more inputs, we would get the m-dimensional equivalent of a line, which is called an m-dimensional hyperplane.

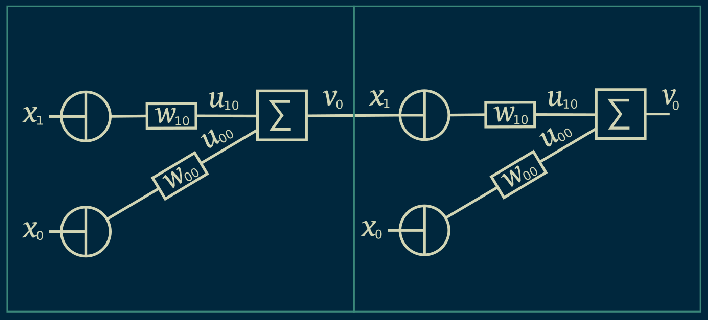

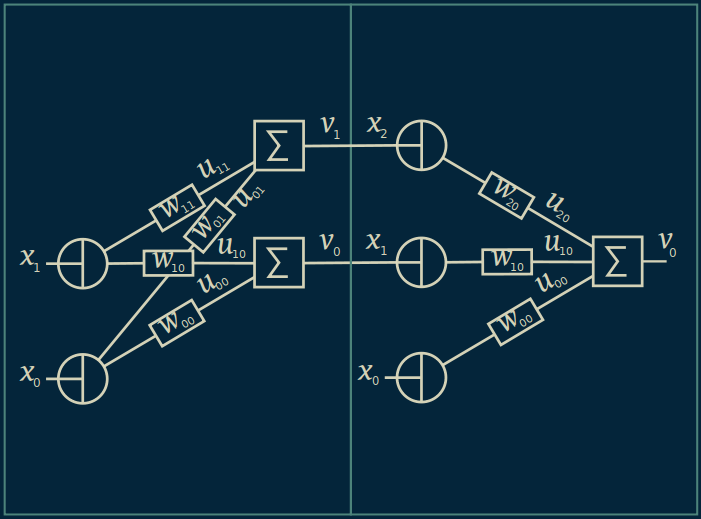

So far so good. Now we can start to get fancier. Our input, x_1, looks a lot like our output, v_0. In fact, there is nothing to prevent us from taking our output and then using it as an input to another network like this one.

Now we have two separate identical layers. We can add a subscript Roman numeral I and a subscript Roman numeral II to our equations depending on which layer we are referring to. And we just have to remember that our x_1 in layer two is the same as our v_0 in layer one.

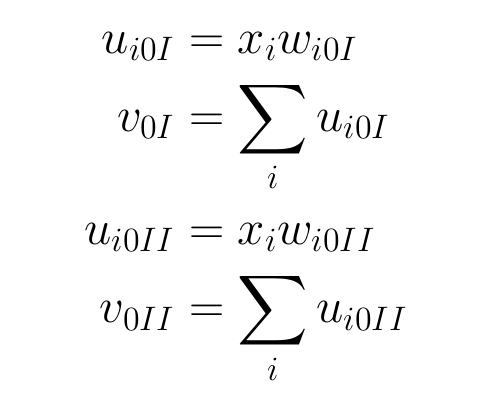

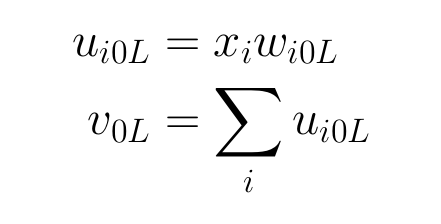

Because these equations are identical, and each of our layers work just the same, we can reduce this to one set of equations, adding a subscript capital L to represent which layer we’re talking about. As we continue here, we will be assuming that all the layers are identical, and to keep the equations cleaner, will leave out the L. But just keep in mind that if we are going to be completely correct and verbose, we would add the L subscript onto the end of everything to specify the layer it belongs to.

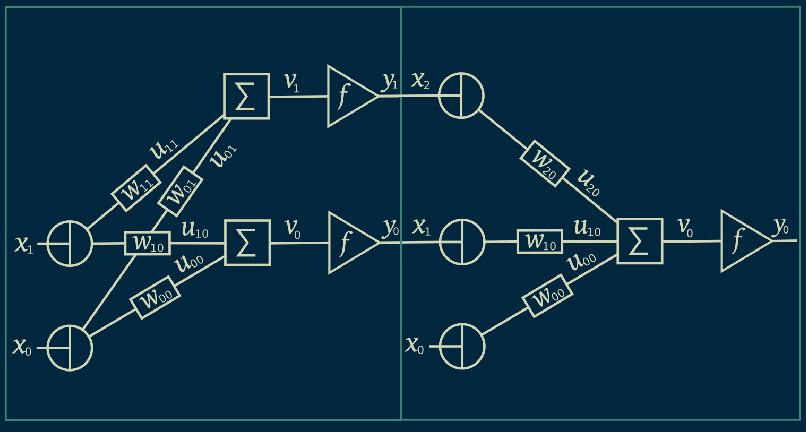

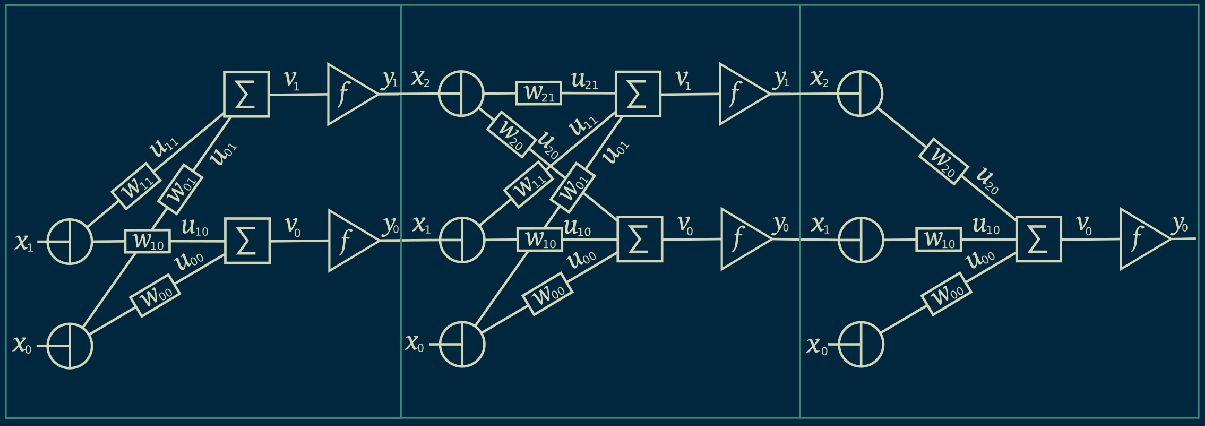

Now that we have two layers, there is no reason that we can’t connect them in more than one place. Instead of our first layer just generating one output, we can make several outputs. In our diagram, we will add a second output, v_1. And we will connect this to a third input into our second layer, x_2. Keep in mind that the x_0 input to every layer will always be equal to one. That bias node shows up again in every layer.

Now there are two nodes shared by both layers. We can modify our equations accordingly, to specify which of the shared nodes we are talking about. They behave exactly the same, so we can be efficient and reuse our equation, but we can specify subscript j to indicate which output we are talking about. So now if I am connecting the ith input to the jth output that i and j will determine which weight is applied and which u's get added together to create the output v_j.

And we can do this as many times as we want. We can add as many of these shared nodes as we care to. The model as a whole only knows about the input x_1 into the first layer and the output v_0 of the last layer. From the point of view of someone sitting outside the model, the shared nodes between layer one layer two are hidden. They are inside the black box. Because of this, they are called hidden nodes.

We can take this two layer linear network, create 100 hidden nodes, set all of the weights randomly, and see what model is it produces. Even after adding all of this structure, the resulting models are still straight lines. In fact, it doesn’t matter how many layers you have and how many hidden nodes each layer has, any combination of these linear elements with weights and sums will always produce a straight line result. This is actually one of the traits of linear computation that makes it so easy to work with. Unfortunately for us, it also makes really boring models. Sometimes a straight line is good enough, but that’s not why we go to neural networks. We’re going to want something more sophisticated.

Logistic regression

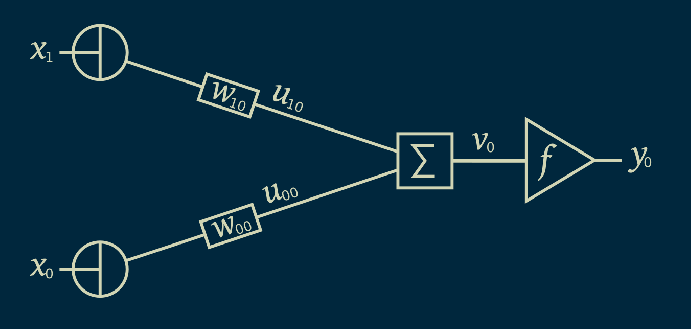

In order to get more flexible models, we are going to need to add some nonlinearity. We will modify our linear equation here. After we calculate our output v_0, we subject it to another function f(), which is not linear, and we'll call the result y_0.

One really common non-linear function to add here is the logistic function. It is S shaped, so sometimes it is called a sigmoid function too, although that can be confusing, because technically any function shaped like an S is a sigmoid.

We can get a sense what logistic functions look like by choosing random weights for this one input, one output, one layer network and meeting the family.

One notable characteristic of logistic functions is that they live between zero and one. For this reason, they are also called squashing functions. You can imagine taking a straight line and then squashing the edges and bending them down so that the whole thing fits between zero and one no matter how far out you go.

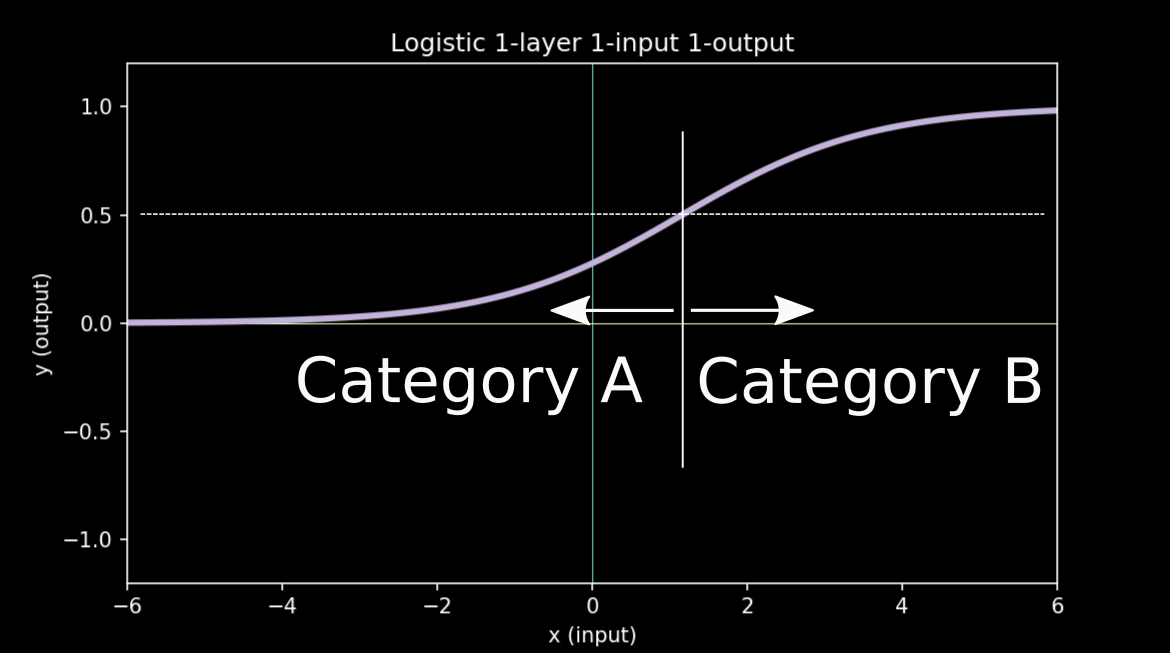

Working with logistic functions brings us to another connection with machine learning models, logistic regression. This is a bit confusing, because regression refers to finding a relationship between input and output, usually in the form of a line or curve of some type. Logistic regression is actually used a classifier most of the time. It finds a relationship between a continuous input variable and a categorical output variable. It treats observations of one category as zeros, and treats observations of the other category as ones, and then find the logistic function that best fits all those observations.

To interpret the model, we add a threshold, often around .5, and wherever the curve crosses the threshold there is a demarcation line. Everything to the left of that line is predicted to fall into one category and everything to the right of that line is predicted to fall into the other. This is how a regression algorithm gets modified to become a classification algorithm.

As with linear functions, there’s no reason not to add more inputs. We know that logistic regression can work with many input variables, and we can represent that in our graph as well. Here we just add one, in order to keep the plot three dimensional, but we could add as many as we want.

To see what type of functions this network can create, we can choose a bunch of random values for the weights. As you might have expected, the functions we create are still S shaped, but now three dimensional. They look like a tablecloth laid across two tables of unequal height. Most importantly, If you look at the contour lines projected down onto the floor of the plot, you can see that they are all perfectly straight. The result of this is that any threshold we choose for doing classification will split our input space up into two halves, with the divider being a straight line. This is why logistic regression is described as a linear classifier. Whatever the number of inputs you have, whatever dimensional space you are working in, logistic regression will always split it into two halves using a line or a plane or hyperplane of the appropriate dimensions.

Perceptrons

Another popular non-linear function is the hyperbolic tangent. It is closely related to the logistic function, and can be written in a very symmetric way.

We can see, when we choose some random weights and look at examples, that hyperbolic tangent curves look just like logistic curves, except that they vary between minus one and plus one.

Just like we tried to do before with linear functions, we can use the output of one layer as the input to another layer. We can stack them in this way and we can even add hidden nodes the same way we did before. Here we just show two hidden nodes, in order to keep the diagram simple, but we can add as many as we want.

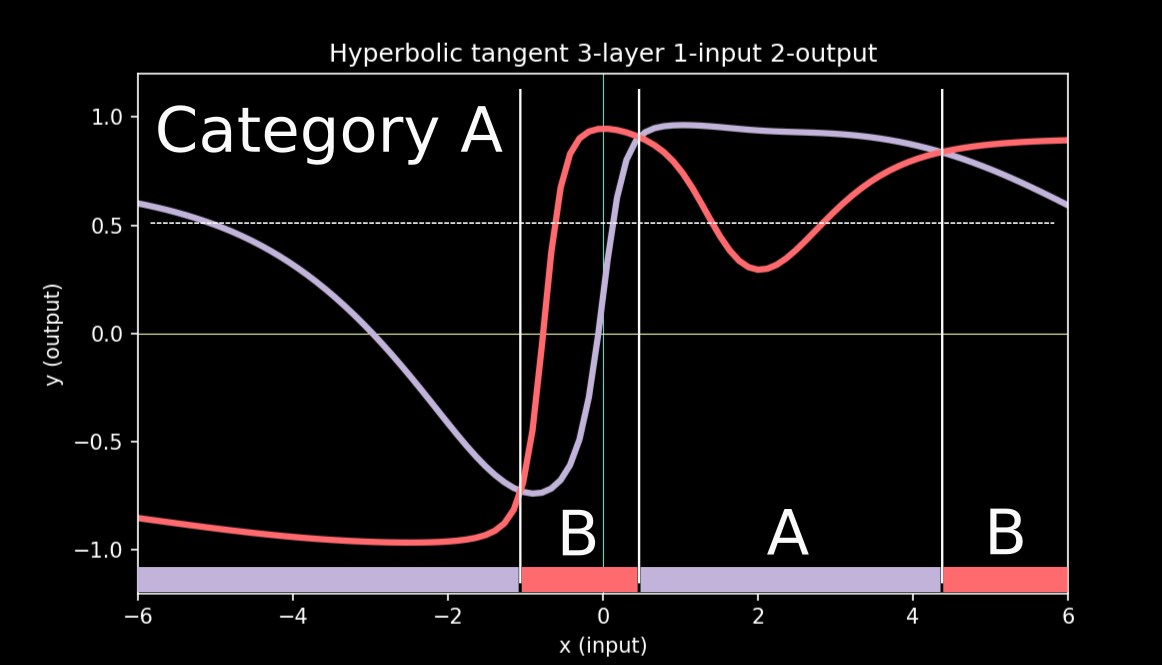

When we choose random weights for this network and look at the output, we find that things get interesting. We have left the realm of the linear. Because hyperbolic tangents are non-linear, when we add them together we get something that doesn’t necessarily look anything like a hyperbolic tangent. We get curves, wiggles, peaks, valleys, a much wider variety of behavior then we saw with single layer networks.

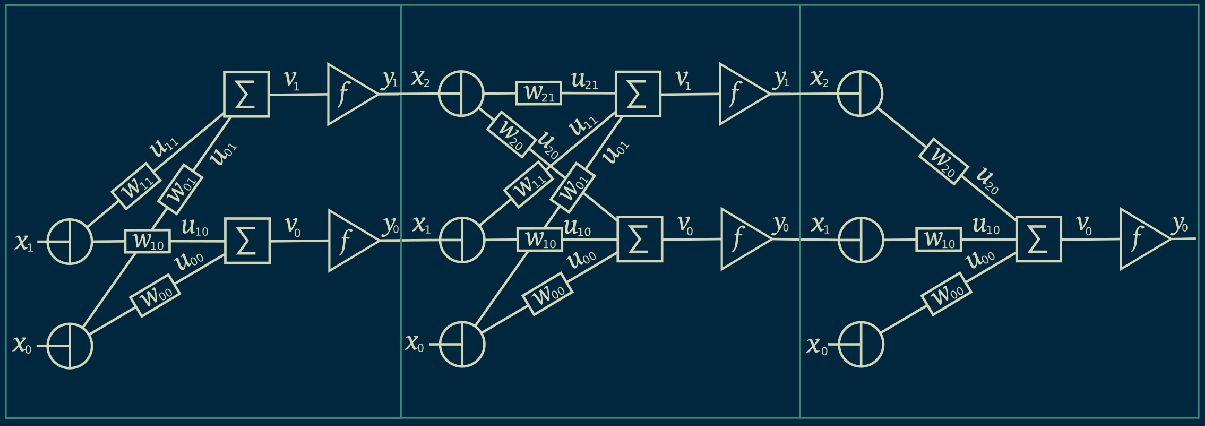

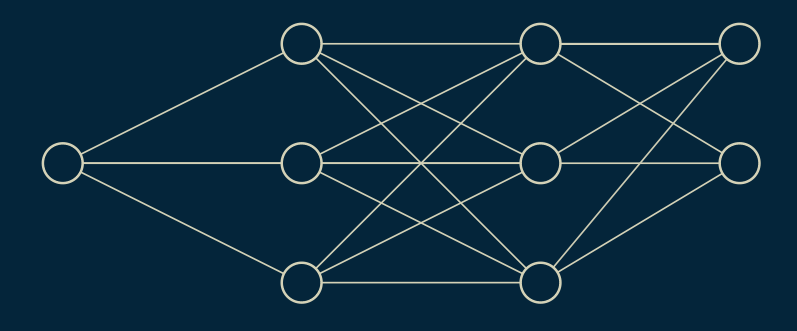

We can take the next step, and add another layer to our network. Now we have a set of hidden nodes between layer one in layer two and another set of hidden nodes between layer two and layer three.

Again we choose random values for all the weights and look at the types of curves it can produce. Again, we see wiggles, peaks, valleys, and a broad selection of shapes. If it is hard to tell the difference between these curves and the curves generated by a two layer network, that is because they are mathematically identical. We won’t try to prove it here, but there is a cool result that shows that any curve you can create using a many layered network, you can also create using a two layered network, as long as you have enough hidden nodes. The advantage of having a many layered network is that it can help you create more complex curves using fewer total nodes.

For instance, in our two layer network we used a hundred hidden nodes. In our three layer network we used 11 hidden nodes in the first layer and nine hidden nodes in the second layer. That’s only a fifth of the total number we used in the two layer network, but the curves it produces show similar richness.

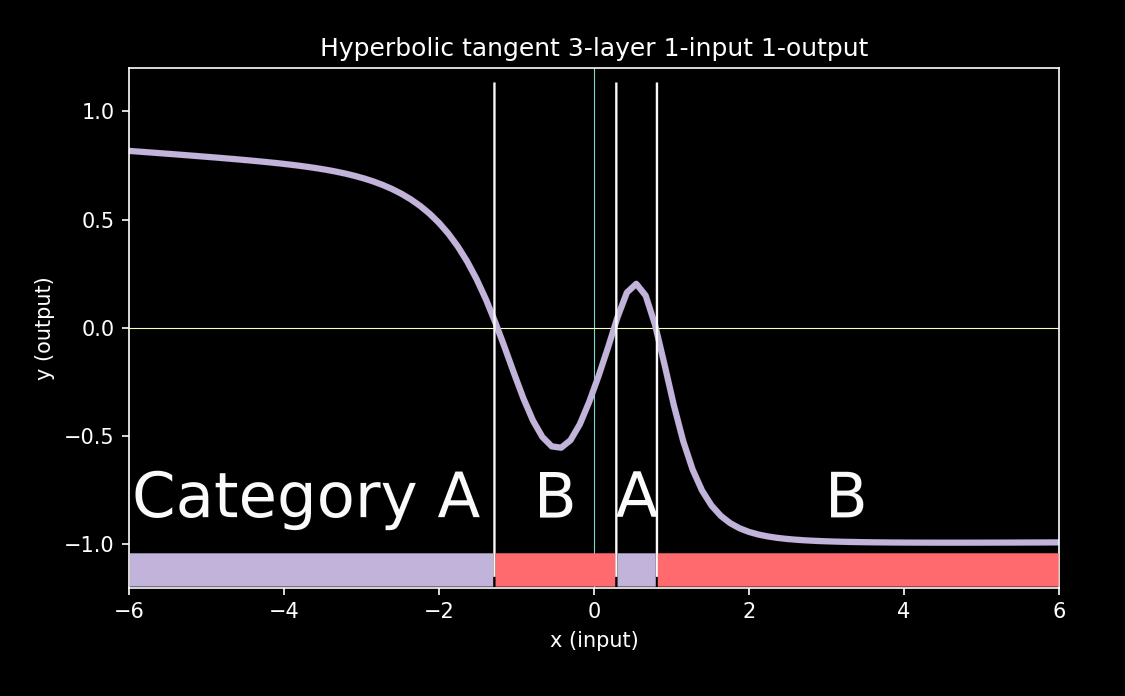

We can use these fancy wiggly lines to make a classifier, as we did with logistic regression. Here, we use the zero line as the cutoff. Everywhere that our curve crosses the zero line there is a divider. In every region that the curve sits above the zero line, we'll call this Category A. Similarly, everywhere the curve is below the zero line, we have Category B.

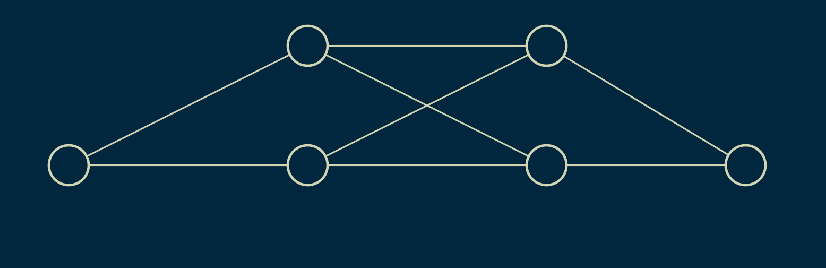

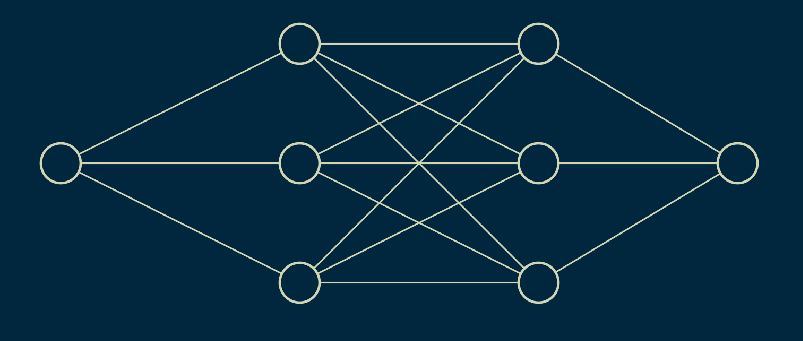

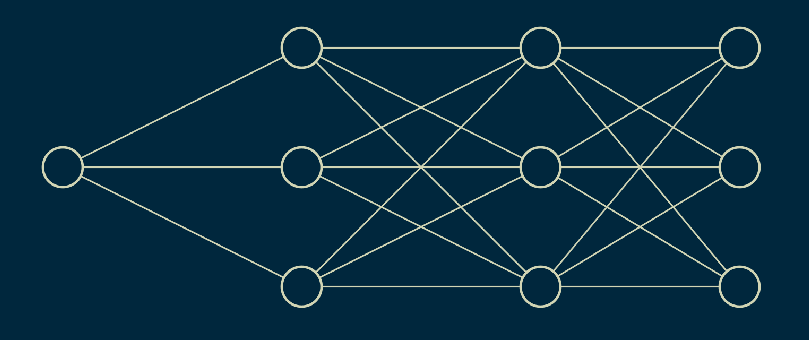

What distinguishes these nonlinear classifiers from linear ones is that they don’t just split the space into two halves. In this example, regions of A and B are interleaved. Building a classifier around a multi-layer nonlinear network gives it a lot more flexibility. It can learn more complex relations. This particular combination of multi-layer network with hyperbolic tangent non-linear function has its own name, a multi-layer perceptron. As you can guess, when you only have one layer, it's just called a perceptron. In that case, you don't even need to add the non-linear function to make it work. The function will still cross the x axis at all the same places. Here is the full network diagram of a multi-layer perceptron.

Fully-connected neural networks

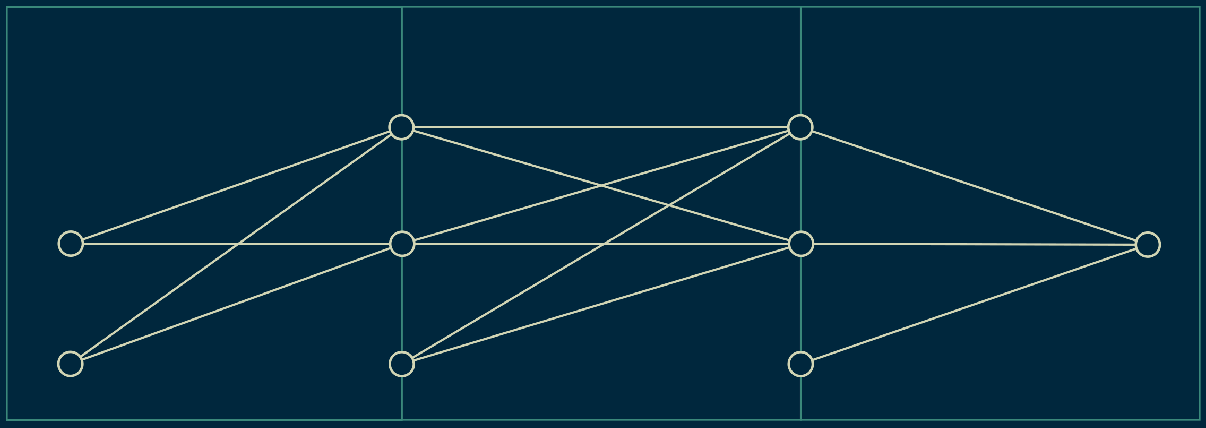

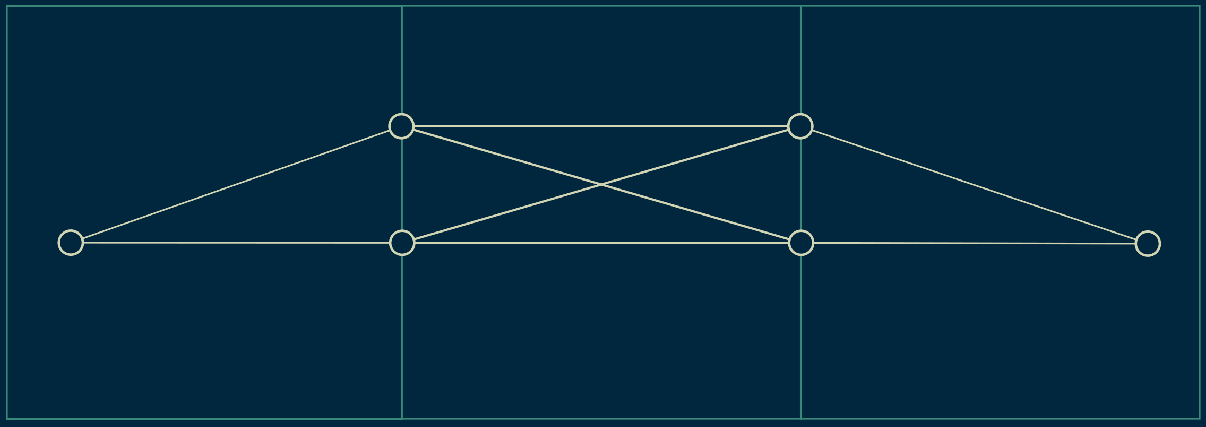

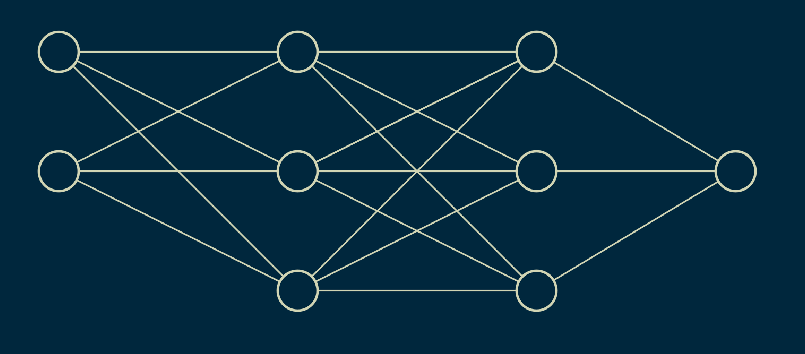

This representation is helpful because it makes every single operation explicit. However, it’s visually cluttered and difficult to work with. Because of this, it's most often simplified to look like circles connected by lines. This implies all of the operations that we saw in the previous diagram. Connecting lines each have a weight associated with them. Hidden nodes and output nodes perform summation and nonlinear squashing. But in this diagram all of that is implied.

In fact, our bias nodes, the nodes that always have a value of one in each layer, are also left out most of the time. So our original network reduces to this. The bias nodes are still present, and their operation hasn’t changed at all, but they are omitted for visual clarity.

We only show two hidden nodes from each layer here, but in practice we used quite a few more. Again, to make the diagram as clean as possible, we often don’t show all the hidden nodes, we just show a few, and the rest are implied.

Here is a generic diagram then for a three layer single input, single output network. Notice that if we specify the number of inputs, the number of outputs, the number of layers, and the number of hidden nodes in each layer, we can fully define our neural network.

We can also take a look at a two input, single output neural network.

Because it has two inputs, its outputs will be a three dimensional curve. We can once again choose random weights and generate curves to see what types of functions this neural network might be able to represent.

This is where it really gets fun. With multiple inputs, multiple layers, and nonlinear activation functions, neural networks can make really crazy shapes. It’s almost correct to say that they could make any shape you want. It’s worth taking a moment to notice what its limitations are.

First, notice that all of the functions fall between plus and minus one. The dark red and the dark green regions kiss the floor and the ceiling of this range, but they never cross it. This neural network would not be able to fit a function that extended outside of this range.

Also, notice that these functions all tend to be smooth. They have hills and dips and valleys and wiggles even points and wells, but all of it happens relatively smoothly. If we hope to fit a function with many jagged jumps and drops, this neural network might not be able to do a very good job of it.

However, aside from these two limitations, the variety of functions that this neural network can produce is a little mind-boggling.

We modified a single output neural network to be a classifier when we looked at the multilayer perceptron. There is another way to do this. We can use a two output neural network instead.

Outputs of a three layer, one input, two output neural network look like this. We can see that in many cases the two curves cross and in some instances take they cross in several places.

We can use this to make a classifier. Wherever the one output is greater than another, it can signify that one category dominates another. Graphically, wherever the two output functions cross, we can draw vertical line. This chops up the input space into regions. In each region one output is greater than the other. For instance, wherever the blue line is greater, we can assign that to be category A. Then, wherever the peach colored line is greater, those regions are category B. Just like a multilayer perceptron, this lets us chop the space up in more complex ways than a linear classifier could. Regions of category A and category B can be shuffled together arbitrarily.

When you only have two outputs, the advantages of doing it this way over a multilayer perceptron with just one output are not at all clear. However, if you move to three or more outputs, the story changes.

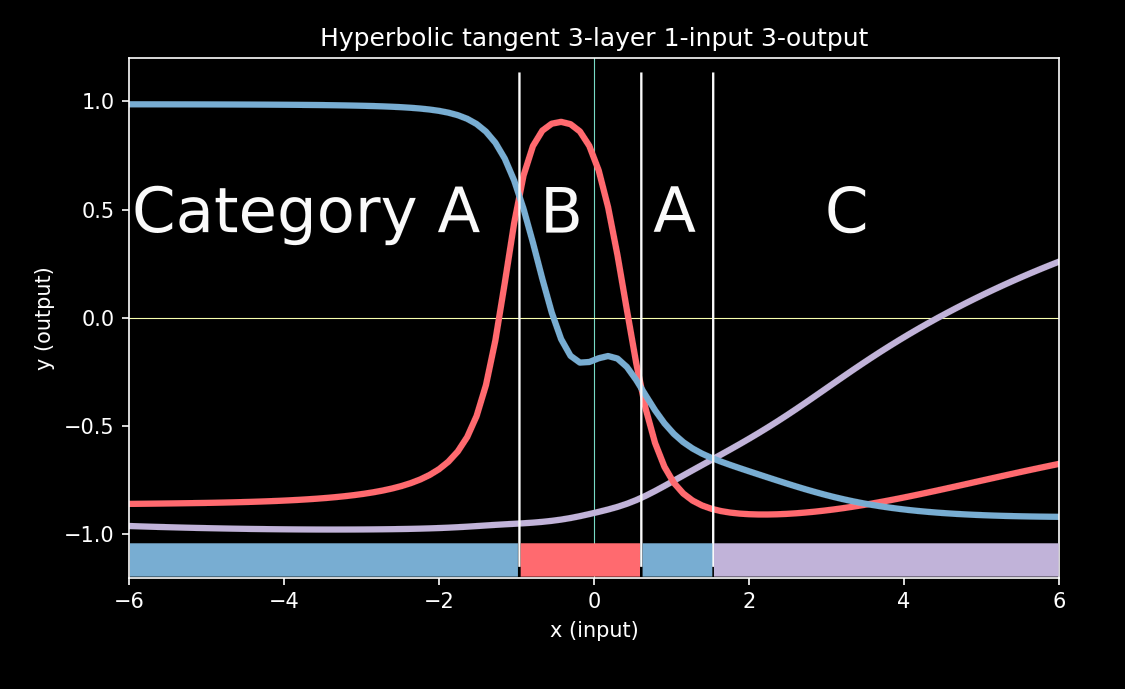

Now, we have three separate output functions.

We can use our same criterion of letting the function with the maximum value determine the category. We start by chopping up the input space according to which function has the highest value. Each function represents one of our categories. We’re going to assign our first function to be category A, and label every region where it is greatest as category A. Then we can do the same with our second function and our third.

Using this trick, we are no longer limited to two categories. We can create as many output nodes as we want, and learn and chop up the input space into that many categories. It's worth pointing out that the winning category may not be the best by very much. In some cases they are very close. One category will be declared the winner, but the next-runner up may be almost as good a fit.

There is no reason that we can’t extend this approach to two or more inputs. Unfortunately it does get harder to visualize. You have to imagine several of these lumpy landscape plots on top of each other. In some regions, one will be greater than the others. In that region, that category associated with that output will be dominant.

To get a qualitative sense for what these regions might look like, you can look at the projected contours on the floor of these plots. In the case of a multi layer perceptron, these plots are sliced at the y = 0 level. That means, if you look at the floor of the plot, everything in any shade of green will be one category and everything in any shade of red will be the other category.

The first thing that jumps out about these category boundaries is how diverse they are. Some of them are nearly straight lines, albeit with a small wiggle. Some of them are wilder bends and curves. And some of them chop the input space up into several disconnected regions of green and red. Sometimes there is a small island of green or an island of red in the middle of a sea of the other color. The variety of boundaries is what makes this such a powerful classification tool.

The one limitation we can see looking at it this way is that the boundaries are all smoothly curved. Sometimes those curves are quite sharp, but usually they are gentle and rounded. This shows the natural preference that neural networks with hyperbolic tangent activation functions has for smooth functions and smooth boundaries.

Takeaways

The goal of this exploration was to get an intuitive sense for what types of functions and category boundaries neural networks can learn when used for regression or classification. We have seen both their power, and their distinct preference for smoothness. We have only looked at two nonlinear activation functions, logistic and hyperbolic tangent, both of which are very closely related. There are lots of others, and some of them do a bit better at capturing sharp nonlinearities. Rectified linear units (ReLU's), for instance, produce surfaces and boundaries that are quite a bit sharper. But my hope was to seed your intuition with some examples of what’s actually going on under the hood when you train your neural network.

Here are the most important things to walk away with:

- • Neural networks learn functions, and can be used for regression. Some activation functions limit the output range, but as long as that matches the expected range of your outputs it's not a problem.

- • Neural networks are most often used for classifiation. They've proven good at it.

- • Neural networks tend to create smooth functions when used for regression, and smooth category boundaries when used for classification.

- • For fully connected (vanilla) networks, a two-layer network can learn any function a deep (many-layered) network can learn, however a deep network might be able to learn it with fewer nodes.

- • Making sure that inputs are normalized (have a mean of near zero and a standard deviation of less than one) helps neural networks to be more sensitive to their relationships.

I hope this helps as you jump into your next project. Happy building!

Production notes

- The code for generating the plots and gif frames is all in python, using numpy and matplotlib. The neural network code is from scratch.

- The gifs were generated using FFmpeg, called from python scripts.

- The drawings are .png format, exported from .svg format, which were created in Inkscape.

- The equations were generated in LaTeX, and rendered using pdflatex.

- Color palette is Retro Rocks from SlideStream.

- All the code, images, and gifs are freely available under the MIT license in this GitHub repository.